Dear friends,

Welcome to the December Mutual Fund Observer, and to the holiday season.

The Christmas of the early American republic would be barely recognizable to us. In many colonies, it was a workday, ignored or mistrusted; only some immigrant communities treated it as a true festival. You’ll remember the Christmas of 1776, when George Washington forced his army across the ice‑clogged Delaware and struck the Hessian garrison at Trenton, counting on an enemy shaped by a Christmas‑keeping culture facing an army for whom December 25 was, at best, optional.

Between the founding of the Republic and 1820, New England’s premier newspaper – The Hartford Courant – had neither a single mention of Christmas-keeping nor a single ad for holiday gifts. In Pennsylvania, the Harrisburg Chronicle – the newspaper of the state’s capital – ran only nine holiday advertisements in a quarter century, and those were for New Year’s gifts. The great Presbyterian minister and abolitionist orator Henry Ward Beecher, born in 1813, admitted that he knew virtually nothing about Christmas until he was 30: “To me,” as a child, he wrote, “Christmas was a foreign day.” In 1819, Washington Irving, author of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Rip van Winkle, mourned the passing of Christmas. And, in 1821, the anonymous author of Christmas-keeping lamented that “In London, as in all great cities … the observances of Christmas must soon be lost.” Though he notes, “Christmas is still a festival in some parts of America.”

Why? At base, Christmas was suppressed by the actions and beliefs of just two groups: the rich people… and the poor people.

The rich, the Protestant descendants of the founding Puritans, concentrated in the booming commercial and cultural centers of the Northeast, reviled Christmas as pagan and unpatriotic. About which they were at least half right: pagan certainly, unpatriotic… ehhh, debatable.

Here we seem to have a contradiction in terms: a pagan Christmas. To resolve the contradiction, we need to separate a religious celebration of Christ’s birth from a celebration of Christ’s birth on December 25th. Why December 25th? The most important piece of the puzzle is obscured by the fact that we use a different calendar system – the Gregorian – than the early Christians did. Under their calendar, December 25th was the night of the winter solstice, the darkest day of the year, but also the day on which light began to reassert itself against the darkness. It is an event so important that every ancient culture placed it as the centerpiece of their year. We have a record of at least 40 holidays taking place on, or next to, the winter solstice. Our forebears rightly noted that the choice of December 25th was a calculated marketing decision meant to draw pagans away from one celebration (Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, the birthday of the Invincible Sun) and into another.

So the Puritans were correct when they pointed out – and they pointed this out a lot – that Christmas was simply a pagan feast in Christian garb. Increase Mather found it nothing but “mad mirth…highly dishonorable to the name of Christ.” Cromwell’s Puritan parliament banned Christmas-keeping in the 1640s, and the Massachusetts Puritans did so in the 1650s.

And while the legal bans on Christmas could not be sustained, the social ones largely were.

The rich, who didn’t party, were a problem. The poor, who did, were a far bigger one.

There was, by long European tradition, a period of wild festivity to celebrate New Year’s. Society’s lowest classes – slaves or serfs or peasants or blue collar toilers – temporarily slipped their yokes and engaged in a period of wild revelry and misrule.

In America, the parties were quite wild. Really quite wild.

Think: Young guys.

Lots of them.

With guns.

Drunk.

Ohhh … way drunk, lots of alcohol, to… uh, drive the cold winter away.

And a sense of entitlement, a sense that their social betters owed them good food, small bribes, and more alcohol.

Then add lots more alcohol.

Roving gangs, called “callithumpian bands,” roamed night after night, by a contemporary account, “shouting, singing, blowing trumpets and tin horns, beating on kettles, firing crackers … hurling missiles” and demanding some figgy pudding. Remember?

Roving gangs, called “callithumpian bands,” roamed night after night, by a contemporary account, “shouting, singing, blowing trumpets and tin horns, beating on kettles, firing crackers … hurling missiles” and demanding some figgy pudding. Remember?

“Oh, bring us a figgy pudding and a cup of good cheer

We won’t go until we get some;

We won’t go until we get some;

We won’t go until we get some, so bring some out here”

Back then, that wasn’t a song. It was a set of non-negotiable demands enforced by rampant vandalism, and the cheery blue flame was a signal of the amount of rum poured over it.

By the early 1800s, this annual eruption of disorder had become intolerable to the emerging urban middle class. New York, Philadelphia, and Boston were growing rapidly, packing different classes into anxious proximity. The old rural rhythms, where the poor could blow off steam in relative isolation, no longer worked when thousands of armed, drunken young men were roaming streets lined with shops and respectable homes. Something had to give.

Perversely, what saved Christmas was its commercialization. Beginning in New York around 1810 or 1820, merchants and civic boosters – notably the New York Historical Society, intent on marketing their city’s Dutch heritage – began ‘discovering’ old New Amsterdam Christmas traditions. Conveniently, these rediscovered customs centered on family gatherings, communal meals, and presents. Lots of presents. The timing was serendipitous: the Industrial Revolution was producing a surplus of manufactured goods that needed buyers, and the middle class was eager for respectable ways to celebrate that didn’t involve armed gangs at the door.

The commercial Christmas was a triumph of the middle class, but also something more valuable. Over a generation, it transformed a celebration of misrule into an occasion for family connection. It helped bridge centuries-old divides between Christian denominations, the Christmas-keepers and the others. Most importantly, it recentered the holiday around children and the future they represented, rather than around young men and the disorder they embodied.

Which brings us, however awkwardly, to why we invest. Not to maximize our portfolios or beat some benchmark. We invest for the same reason the middle class of the 1820s desperately needed a new version of Christmas, to create some measure of security and possibility for the people we care about, to bridge the gap between the world as it is and the world we hope to leave behind. The markets will continue their callithumpian revelry – shouting, demanding, hurling missiles. Our job is the quieter, more domestic work: protecting what matters, planning for people we love, and occasionally pausing to acknowledge that we’re doing this together, in defiance of cold and dark and uncertainty.

That seems worth raising a cup of good cheer to, even without the figgy pudding.

In this month’s Observer …

In this issue of the Observer…

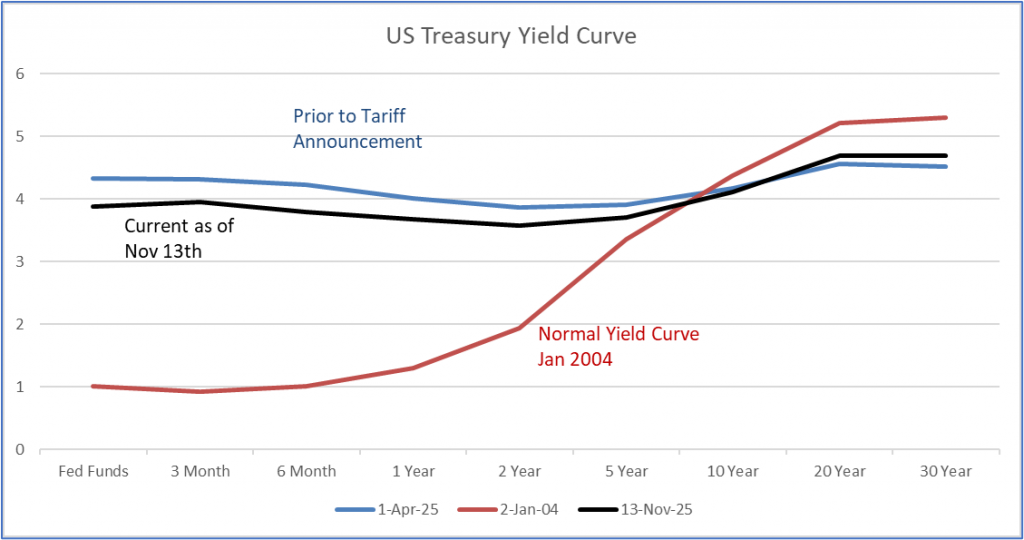

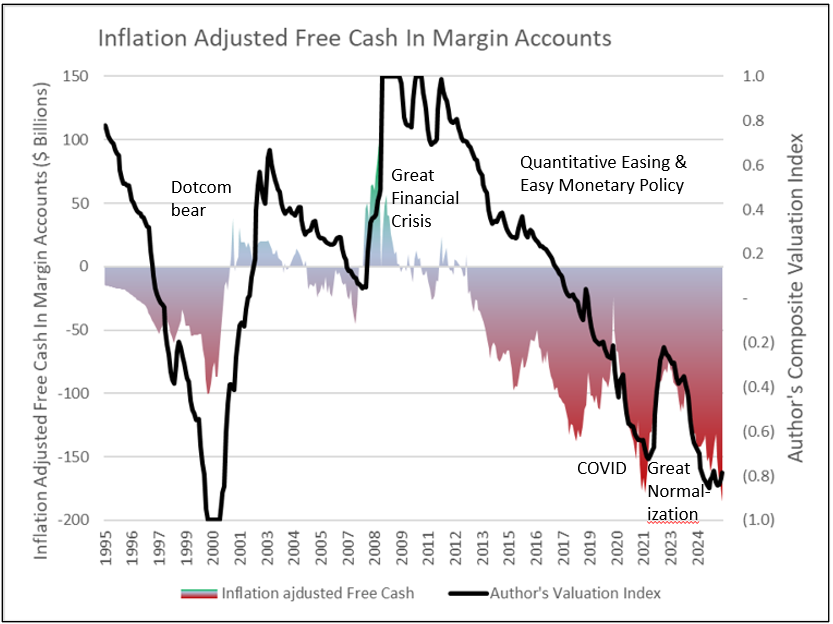

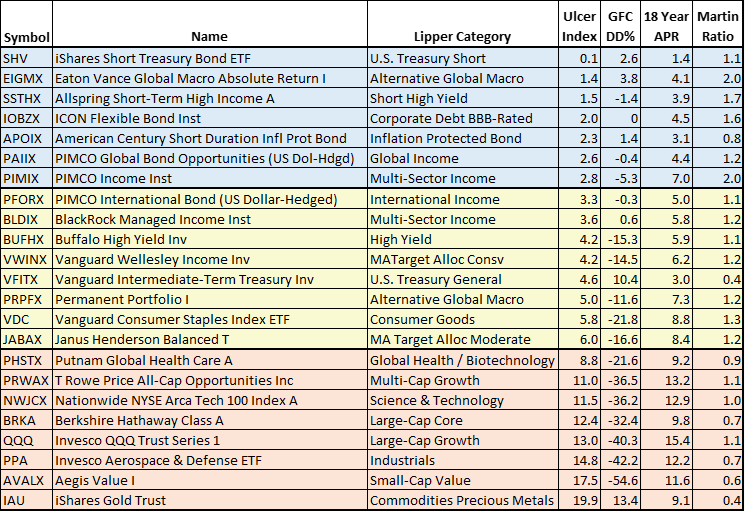

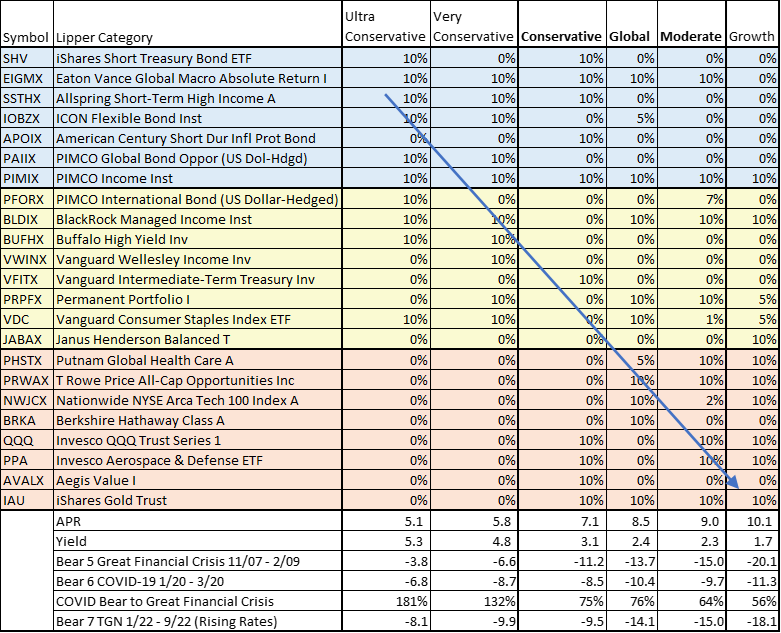

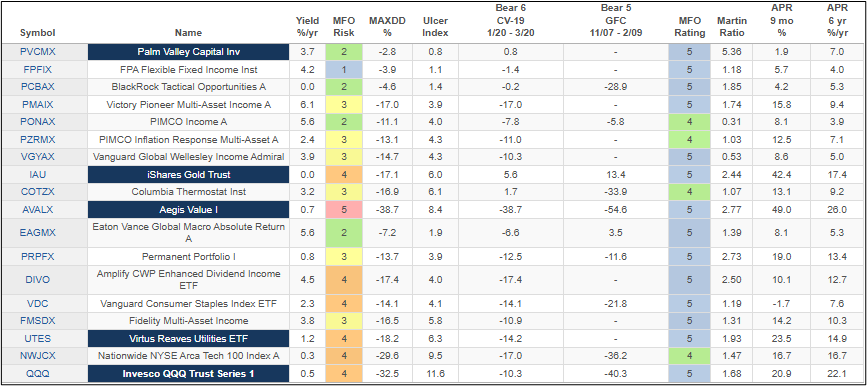

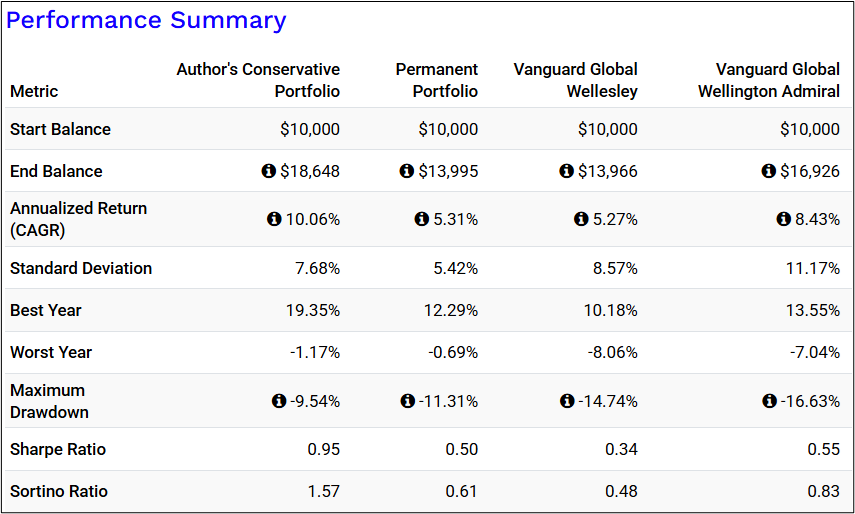

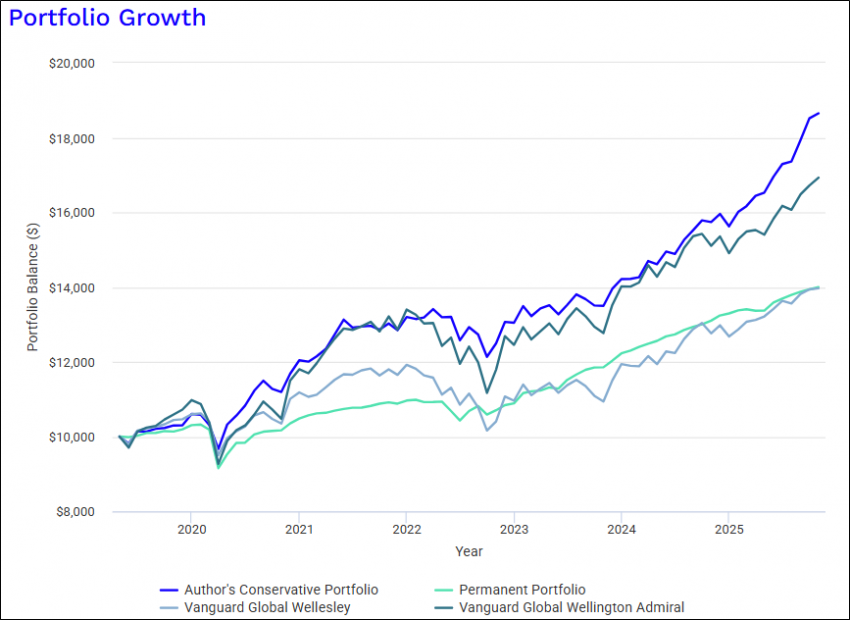

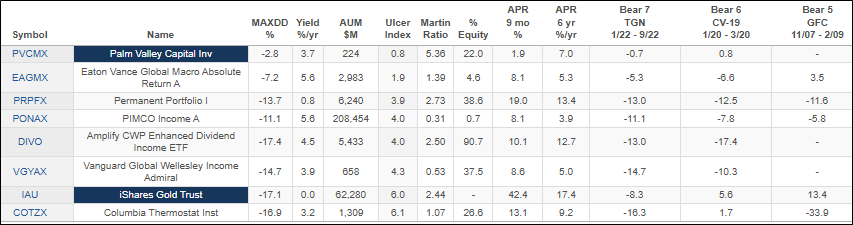

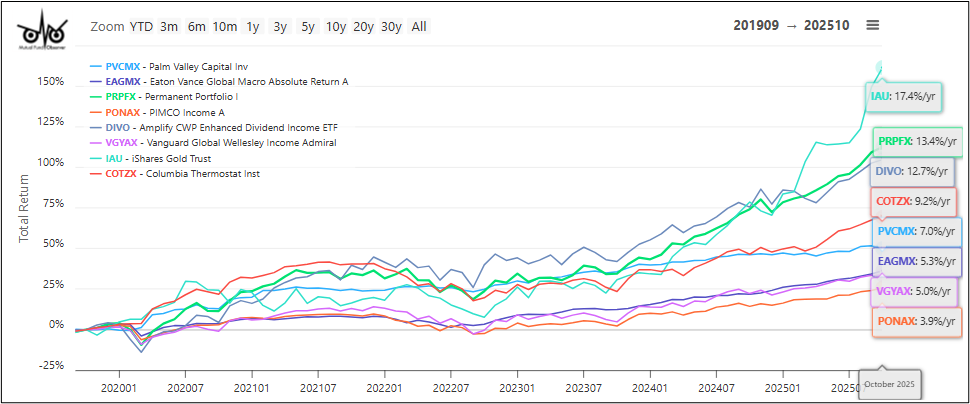

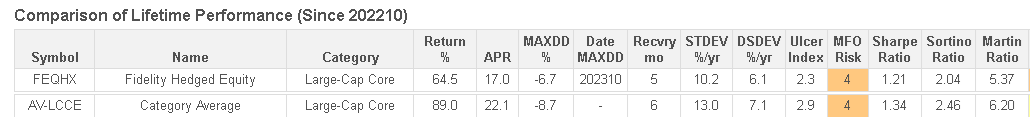

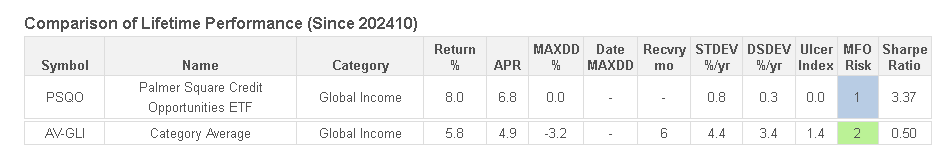

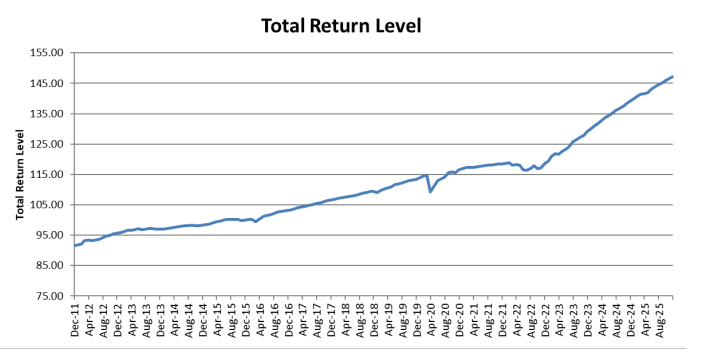

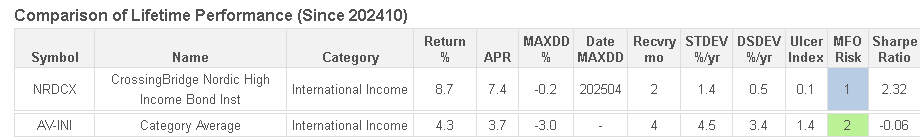

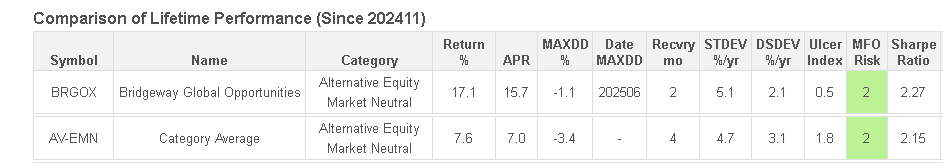

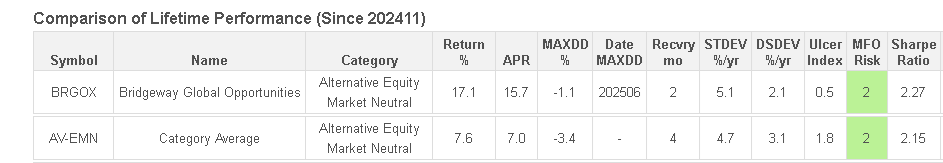

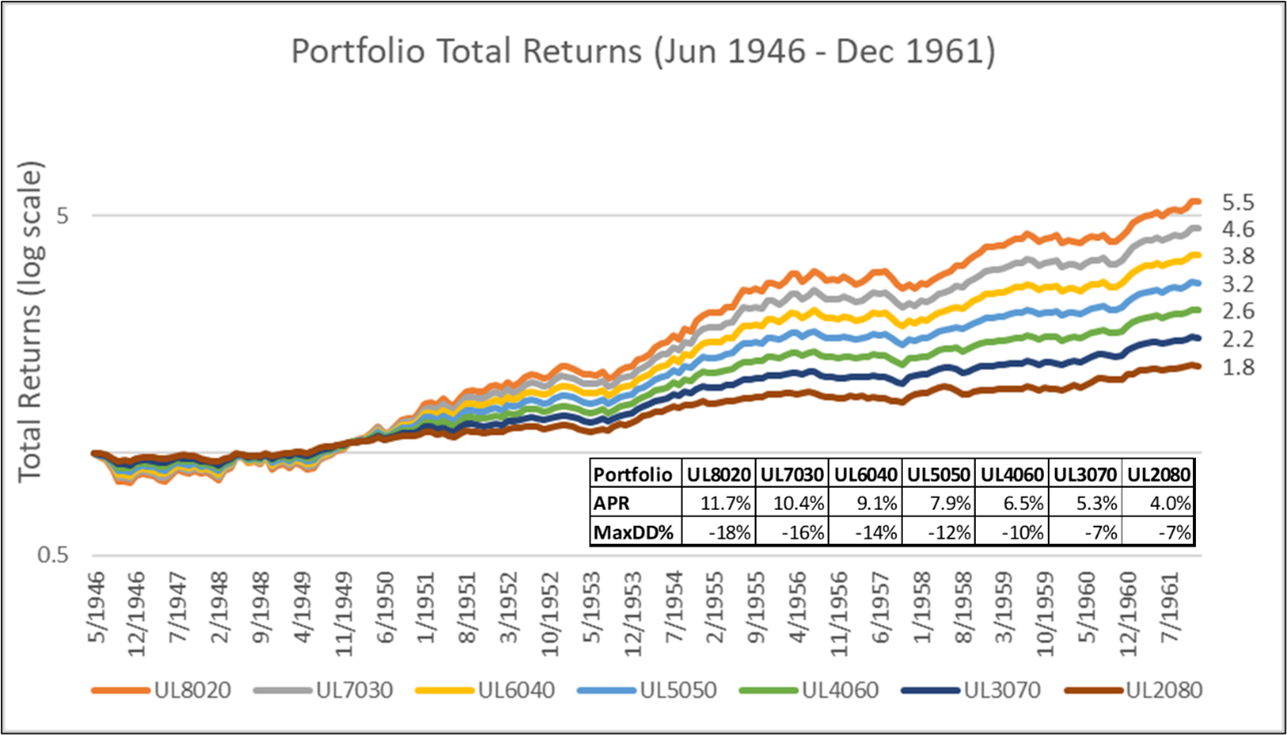

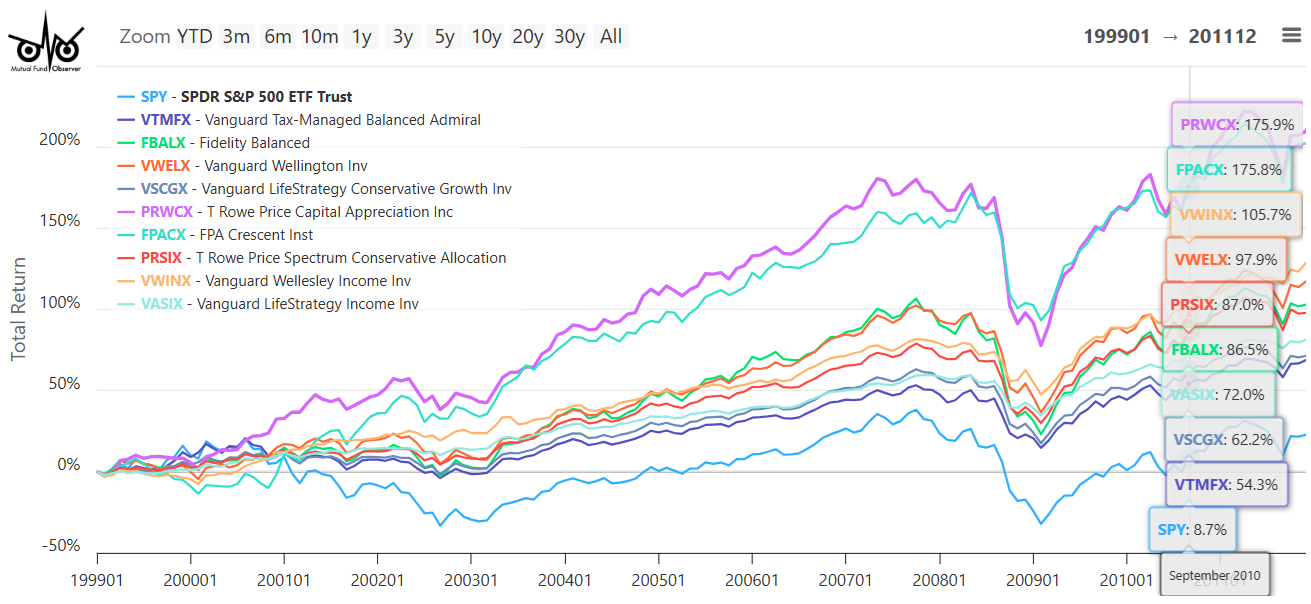

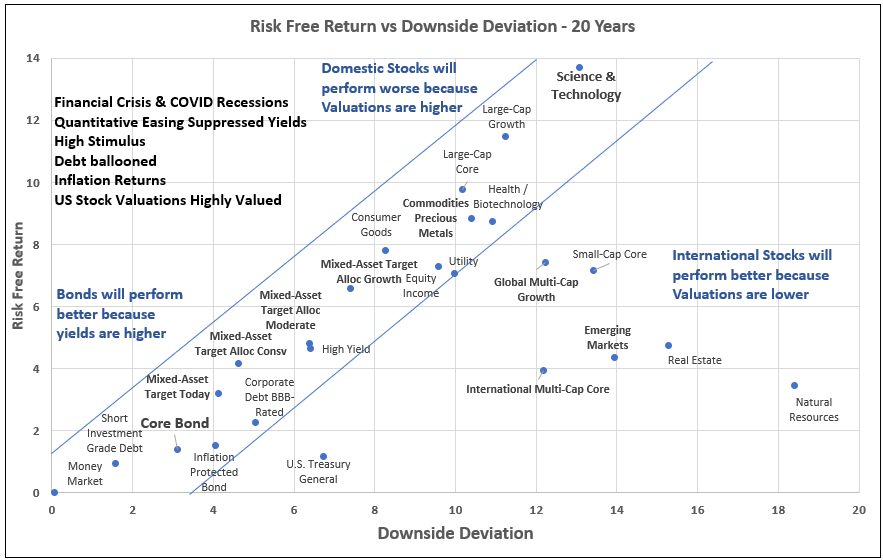

Lynn Bolin examines portfolio construction for an environment where elevated debt levels intersect with longer-term risks of financial crisis and currency devaluation. In “As the World Turns,” he constructs six model portfolios optimized for Great Financial Crisis-level drawdowns while maintaining reasonable returns, deliberately emphasizing recent market behavior—COVID bear market, high inflation, tariff uncertainty—over the less relevant 2022 normalization and 2024 valuation extremes. His conservative portfolio combines established defensive funds like Palm Valley Capital and Columbia Thermostat with tactical managers running light equity exposure, while adding a small gold position he views as overbought short-term but positioned for long-term appreciation through debt monetization.

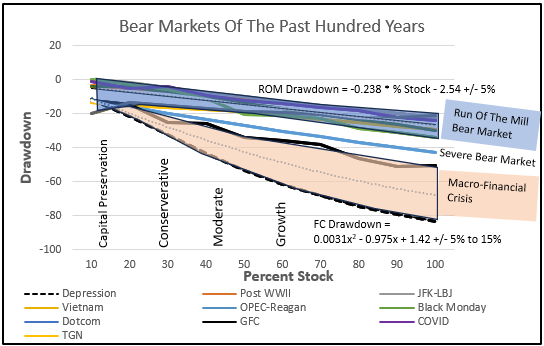

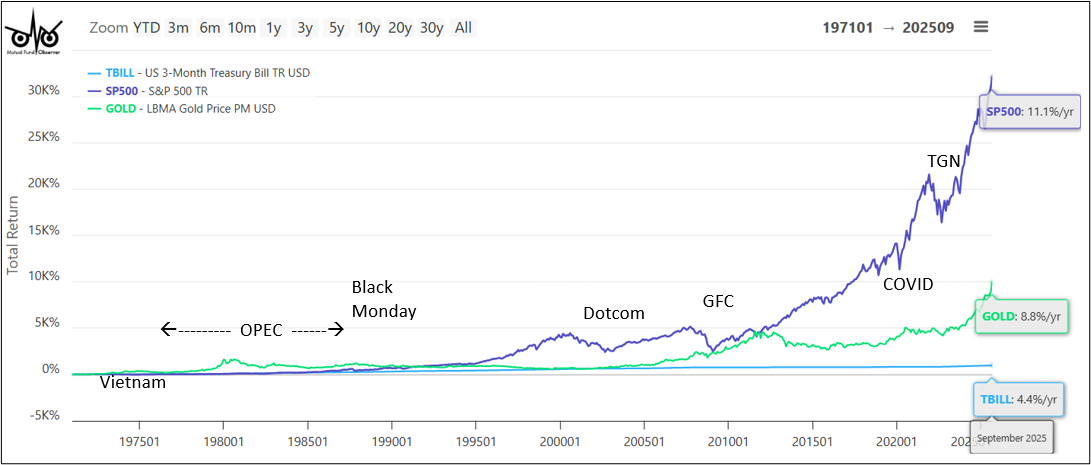

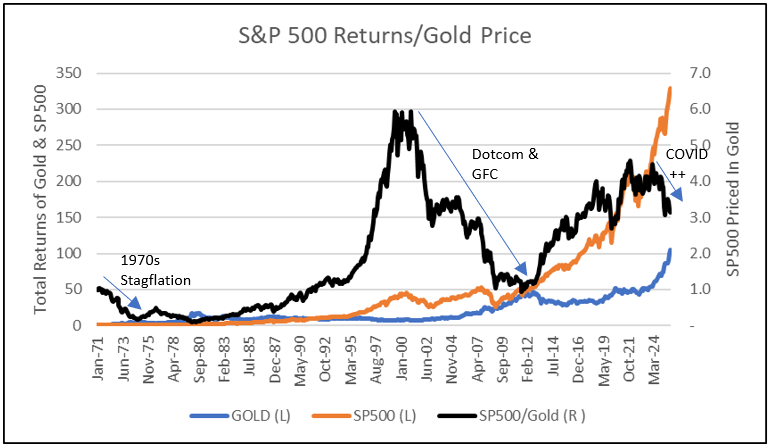

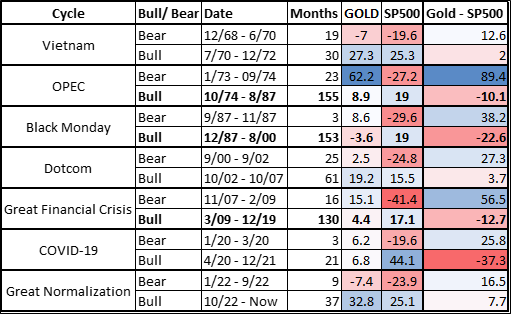

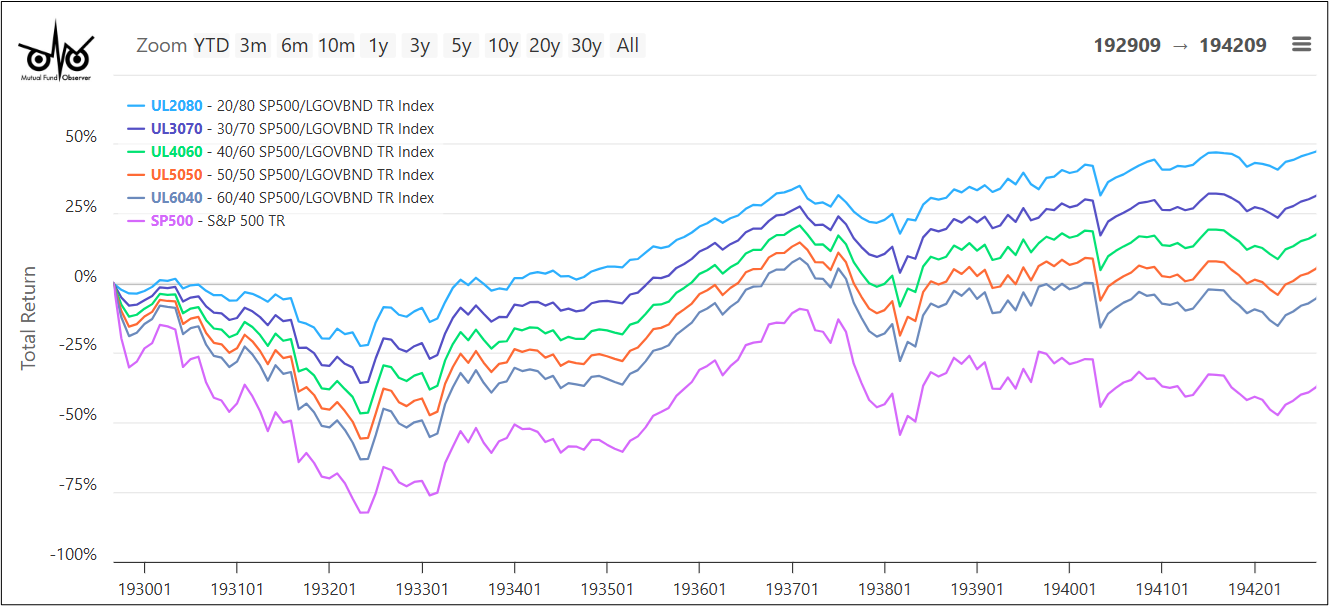

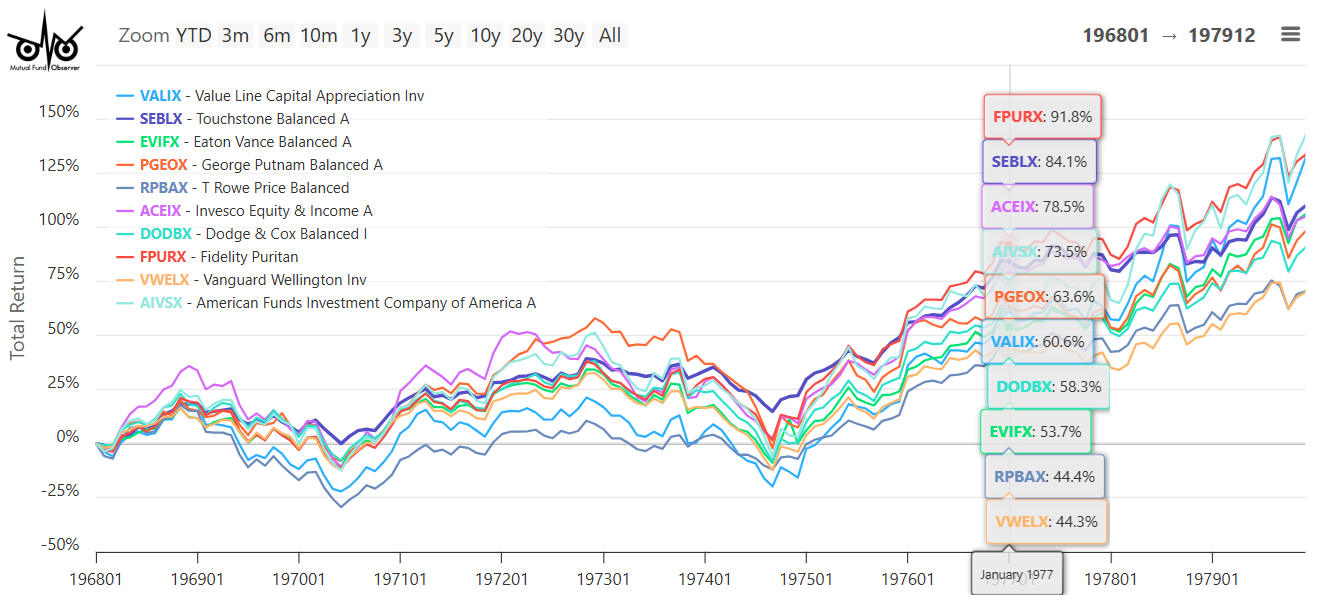

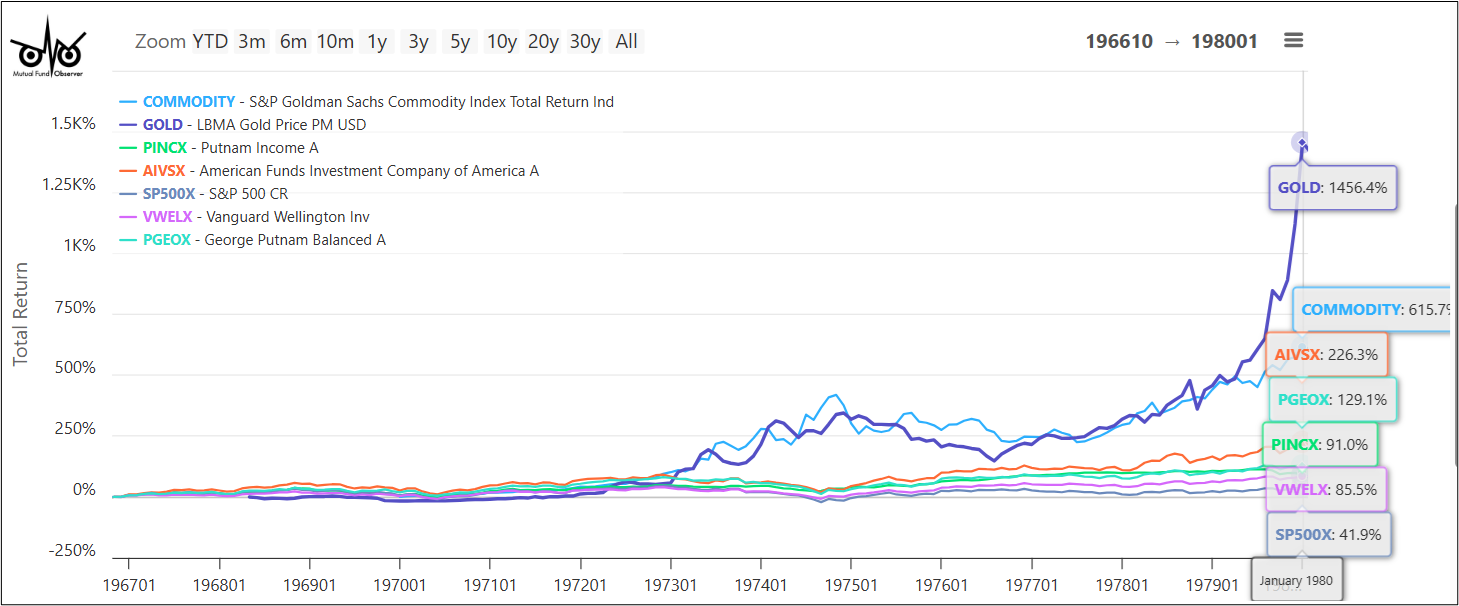

Lynn’s companion piece, “Portfolio Performance During One Hundred Years of Bear Markets,” provides a century-spanning framework for understanding how portfolios behave across market crises. The analysis reveals that mixed portfolios (20-60% equity) recovered within 4-7 years after 1929, while all-stock portfolios didn’t recover before WWII, and that gold has outperformed stocks in every bear market over the past 58 years, particularly during inflationary crises and severe financial dislocations. Lynn concludes that while gold is currently overbought, it offers long-term hedge potential as debt levels approach historical extremes.

Both essays reflect Lynn’s methodical preparation for increased economic uncertainty, combining rigorous quantitative analysis with strategic defensive positioning for a changing debt cycle. They’re worth your time.

I share a Launch Alert for GMO Domestic Resilience ETF, which brings GMO’s 40-plus years of quality investing discipline to companies positioned to benefit from reshoring and nearshoring. The fund represents a tactical bet on a policy-dependent industrial trend, massive commitments through the CHIPS Act, Infrastructure Act, and IRA converging with genuine corporate action and structural cost shifts. Tom Hancock’s team applies the same discipline that has driven GMO’s U.S. Quality strategy to top-tier long-term returns, though this remains satellite positioning rather than core equity exposure.

My second Launch Alert examines MFS Active Mid Cap ETF, portfolio manager Kevin Schmitz’s 17-year mid-cap value strategy now available in an ETF wrapper. The parallel mutual fund has never finished in the bottom quartile in any calendar year since 2009, a testament to consistency rather than heroic outperformance. It’s the kind of fund that earns words like solid, sensible, and reliable: consistent, competent, rarely brilliant, almost never disastrous.

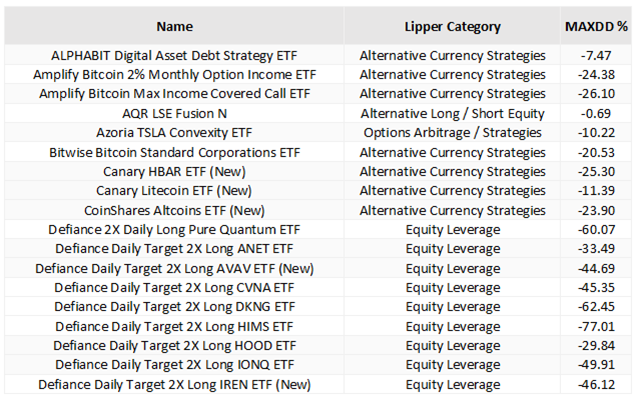

“The Kids are Alright” identifies 10 notable rookies from the 1,087 funds launched through November, separating legitimately interesting opportunities from the 300+ niche trading toys destined to perish in droves. The lowest-risk rookies aren’t experiments; they’re proven managers bringing tested disciplines to investors who couldn’t previously access them, whether through Capital Group’s ETF versions of franchise strategies, T. Rowe Price extending their closed Capital Appreciation discipline into new formats, or GMO bringing institutional deep-value strategies to retail investors.

And The Shadow, as ever, tracks down a horde (perhaps a hoard) of industry developments, including the return of Tiffany Hsiao to Matthews, the conversion of a weird and wonderful fund to a slightly less weird but likely still wonderful ETF, a bunch of fund launches or conversions, and a remarkably long list of liquidations.

When Despair Drives Markets

The US stock market continues its improbable rise through elevated valuations and mounting economic uncertainty. More troubling still: that rise is paced not by the market’s highest-quality companies but by its lowest-quality ones. Something fundamental has shifted.

The evidence points to a phenomenon commentators call “financial nihilism,” a rational response by young investors to an economy that has locked them out. Three in ten Gen Z have abandoned hopes of homeownership. The median age of first-time homebuyers hit an all-time high of 40 this year, up from the low 30s a generation ago. Stagnant wages, crushing student debt, and housing costs that have outpaced income growth by 60% since 1985 have made traditional paths to security seem unattainable. The response: swing for the fences. Meme stocks, leveraged ETFs, crypto derivatives, prediction markets where you can bet on everything from Fed decisions to Taylor Swift’s pregnancy—anything offering moonshot potential over steady accumulation. Monthly wagers on platforms like Polymarket and Kalshi now exceed $1 billion.

Meanwhile, veteran investor Louis Navellier surveys an economy where “the Fed’s been backed into a corner,” companies navigate surging tariffs, and “many households are increasingly struggling to make ends meet as layoffs rise and pay raises shrink,” and offers his assessment for 2026 in two words: “economic nirvana.”

Economic nirvana?

Damn, dude.

The disconnect is stunning. Wall Street doesn’t live on Main Street, and billionaire advisors don’t navigate the economy their clients face, don’t stand in front of the meat counter wondering what they can afford, and don’t worry about what happens when the money runs out before the month does. When traditional success metrics become unreachable for an entire generation, speculation stops being irrational and starts being a survival strategy.

This dynamic, if it proves to be broadly true, complicates your life and your portfolio. Markets driven by despair don’t correct like markets driven by fundamentals: they extend further, persist longer, and collapse faster. Stocks that capitalism should obliterate instead thrive on social media momentum. An AI bubble of epic magnitude, built on trillion-dollar compute clusters and pure faith, comforts investors rather than terrifying them. Traditional risk metrics break down when the investment thesis is “nothing else will work anyway.”

Many observers have struggled to explain the lagging performance of so-called “quality” strategies—ones that (foolishly) believe that really good businesses are more attractive than really bad ones. Much of what we’ve noted above suggests the driver: folks in despair for their (or America’s or the world’s) future don’t adhere to the adage “slow and steady wins the race.” They’re drawn to the bravado of despair, “go big or go home,” as they pour resources into moonshot assets.

All of which makes the argument for getting out, diversifying deeply into assets uncorrelated with meme-driven momentum, while the getting’s good. Quality will matter again, eventually. But “eventually” offers cold comfort when your retirement timeline doesn’t accommodate a decade-long detour through financial nihilism. We might want to think about the implications of embedding despair as a principle in our children’s lives, which we’ll take up in “The Quality Conundrum” in our January issue.

Thanks from, and to, Warren Buffett

Warren Buffett is remarkable, for his persistence and humility and self-reflection quite as much as for his enormous investment success. On November 10, 2025, he issued what is likely one of his last Thanksgiving letters in which he hints, distantly and without drama, at the fact that his body is failing. He talks, laconically and with humor, about the past and heroes and friends, before closing with a reflection on these latter days and his Thanksgiving wishes for you.

One perhaps self-serving observation. I’m happy to say I feel better about the second half of my life than the first. My advice: Don’t beat yourself up over past mistakes – learn at least a little from them and move on. It is never too late to improve.

Get the right heroes and copy them. You can start with Tom Murphy (former CEO of Capital Cities/ABC and the guy who taught Buffett more about running a business than anyone else); he was the best.

Remember Alfred Nobel, later of Nobel Prize fame, who – reportedly – read his own obituary that was mistakenly printed when his brother died and a newspaper got mixed up. He was horrified at what he read and realized he should change his behavior. Don’t count on a newsroom mix-up: Decide what you would like your obituary to say and live the life to deserve it.

Greatness does not come about through accumulating great amounts of money, great amounts of publicity or great power in government. When you help someone in any of thousands of ways, you help the world.

Kindness is costless but also priceless.

I write this as one who has been thoughtless countless times and made many mistakes but also became very lucky in learning from some wonderful friends how to behave better (still a long way from perfect, however). Keep in mind that the cleaning lady is as much a human being as the Chairman.

I wish all who read this a very happy Thanksgiving. Yes, even the jerks; it’s never too late to change. Remember to thank America for maximizing your opportunities.

But it is – inevitably – capricious and sometimes venal in distributing its rewards.

Choose your heroes very carefully and then emulate them. You will never be perfect, but you can always be better.

Buffett urges his readers to “choose your heroes wisely.” That struck me, particularly in the fraught moment in our nation’s political life and this season when we’re meant to reflect on gratitude and what we owe each other. So I’ll ask: Do you have a hero?

The word hero has become oddly complicated. In contemporary life, we often use it as a category rather than a description — a title automatically conferred on anyone who wears a uniform or holds a certain job. It’s an earnest instinct, born of gratitude and respect. But it can also make the word harder to use for its older purpose: to name a person whose conduct, in a moment of real testing, reveals something exceptional about the human spirit.

That’s not quite the sense I mean here. I’m not using hero as a status or a social honorific. I’m trying to use it in a more personal, more demanding sense to point toward the rare individuals whose choices under pressure illuminate what we might hope to be ourselves.

Perhaps a hero is someone who, in the worst of times, embodies the strength we show only in our best moments.

Do you have a hero?

Not a celebrity, not someone you follow online, not even merely a person you admire for a single virtue, but someone whose conduct under strain inspires you to imagine how you might rise to your own moment of testing. Someone, perhaps, whose spirit you wish you could bestow upon your own children. Someone who would inspire, in a eulogy, the person you most admire to grow misty-eyed and admit, “they were my hero, though I never told them.”

I do, though you’ve likely never heard of him. Frank Minis Johnson (1918-1999). Johnson was born in the hill country in northwest Alabama, son of the only Republican in the Alabama legislature, thrice-decorated veteran of the Normandy invasion, appointed by President Eisenhower first as a US Attorney, where he successfully prosecuted modern-day slavery charges against white farmers, and then as the youngest Federal district judge in the country.

Judge Johnson’s rulings weren’t about a single issue or his personal preferences. They embodied an uncomfortable principle: the law applies to everyone, not just the powerful. He desegregated public parks, schools, facilities, and employment, including the state troopers who’d enforced segregation. He upheld women’s rights to serve on juries and receive equal treatment in the military. He made the Selma to Montgomery march possible by ruling that the state couldn’t bar citizens from public highways their taxes had built.

But his commitment extended beyond civil rights to anyone the powerful had deemed unworthy of legal protection. He ruled that patients committed to mental institutions have a constitutional right to adequate care, that prisoners cannot be confined in facilities unfit for human habitation, that undocumented children have the right to a free public education, and that Georgia’s law criminalizing homosexuality was unconstitutional. The law is the law for all, he insisted—for the mentally ill, the imprisoned, the undocumented, the gay, not just for those with power to enforce their preferences.

On what would have been his 100th birthday, the conservative Federalist Society aired a short documentary on his life in which Johnson explained a fundamental tenet: “I never looked on any desegregation case with moral standards in mind … I wasn’t hired to be a moral judge. I wasn’t hired to be a preacher or an evangelist. I’m hired to apply the law.”

According to the Academy of Achievement, “His former law school classmate, George Wallace, called Johnson an ‘integrating, scallawagging, carpetbagging liar.’ The Ku Klux Klan called him ‘the most hated man in Alabama,’ and white students burned a cross on his lawn. The judge and his family received constant death threats. His elderly mother’s house was bombed – they’d meant it for him – but she escaped injury and refused to move.” Federal marshals provided around-the-clock protection for his family from 1961–1975.

Bill Clinton awarded Johnson a Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1995. Civil-rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. once called him “the man who gave true meaning to the word justice.” Judge Johnson changed the world through the simple, principled, repeated application of the word “no.” As in: no, you may not order soldiers beaten. No, you may not close the roads to the citizens whose labor and taxes built them. No, you may not exclude women from public service for a simple reason of their sex. No, no, no … quiet, reflective, principled, unpopular, unbowed “no.”

Saying “no” to what’s wrong matters, even when—especially when—it’s unpopular, dangerous, and yields no immediate reward.

Do you have a hero? I do, and if you ever wonder why I persist at being sort of quietly disagreeable, perhaps it’s because I have a very peculiar angel on my shoulder.

And thanks to you, now and ever

You’d be surprised at how difficult this section is for us to write, mostly because words so poorly capture the sense of gratitude that your faith inspires in us. To our faithful “subscribers,” Greg, William, the good folks at S & F Advisors, William, Stephen, Wilson, Brian, David, Doug, and Altaf, thanks!

Thanks, as ever, to The Grinch, passing on his way to the Whobilation, who tossed a gift, though not the roast beast—he’s saving that for himself.

This is the fourth anniversary of the passing of my friend, Nick Burnett, who lives in memory yet green. Debbi shared a gift with MFO in his memory.

If you share our sense of gratitude for the blessings that have come to you, this might be an opportune moment to choose to share them with those who struggle. Chip and I have a strong and ongoing commitment to supporting our regional food bank, our community foundation, and keeping folks warm during these winter months.

From Chip, me, and all the folks at the Observer, best wishes for a joyful end to the year. We’ll see you on (or about) New Year’s!